From the moment the NASA briefing begins, it becomes clear

that this comet crash will be anything but uneventful. The Hubble Space

Telescope pictures from the first comet fragment impact are nothing short of

spectacular -- and Fragment A was one of the smaller fragments! Thus begins a weeklong

television drama played out on the NASA Channel, in which scientific progress

-- with all of its discoveries and delays and debates -- will unfold on a daily

basis for all the world to see.

spectacular -- and Fragment A was one of the smaller fragments! Thus begins a weeklong

television drama played out on the NASA Channel, in which scientific progress

-- with all of its discoveries and delays and debates -- will unfold on a daily

basis for all the world to see.

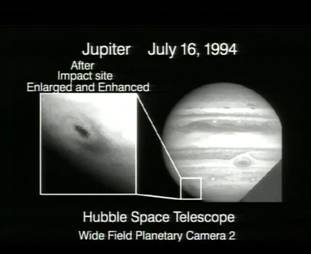

Dr. Heidi Hammel, the Hubble Space Telescope's team leader, begins by discussing an image from the Hubble that is displayed on our screen. It

was taken with the telescope's Wide Field Planetary Camera using a blue filter.

Jupiter appears as a big gray ball. But something dark is visible in the lower

left-hand region -- something that wasn't there yesterday. An enlargement shows

the dark object to be a black spot partially surrounded by some lighter-colored

smudges. This is the impact site of Fragment A, Heidi explains.

According to Heidi, most of the images received thus far

look similar to the one shown, with dark impact features on a light background.

The exception is in the methane band, where the image is reversed and the

impact features look bright.

Later in the briefing we learn that those dark markings in

the impact region are a surprise to scientists. New features on celestial

bodies such as Jupiter are typically bright instead of dark.

The width of the enlarged box is "about two Earth

diameters," Heidi states to my surprise, adding, "so that structure

that you're seeing -- that circular pattern -- is about the size of the Earth!"

The image with the black spot is from the second sweep of

Hubble across Jupiter. Since the Hubble spacecraft orbits the Earth, it cannot

image Jupiter during that half of its orbit when the Earth is blocking its view

of the planet. During the first sweep, the Hubble telescope obtained images of

a bright "plume" that rose some 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) above

the edge of Jupiter after the first impact and then flattened. (A kilometer is

about 0.62137 miles, roughly 5/8 of a mile.) Those images are not available for

release yet, but Heidi says they should be ready tomorrow morning.

Heidi uses a grapefruit-sized globe and a marking pen to

demonstrate the geometry of the comet collisions with Jupiter from the Earth's

vantage point. The globe represents Jupiter, and the pen represents the train

of comet fragments. Heidi holds the globe in one hand and gestures with the pen

in her other hand, pointing it upward at the Jupiter globe and approaching it

from behind at a shallow angle. The comet fragments, she explains, will be

approaching Jupiter's South Pole at an angle and hitting on the far side that

we cannot see.

Heidi uses a grapefruit-sized globe and a marking pen to

demonstrate the geometry of the comet collisions with Jupiter from the Earth's

vantage point. The globe represents Jupiter, and the pen represents the train

of comet fragments. Heidi holds the globe in one hand and gestures with the pen

in her other hand, pointing it upward at the Jupiter globe and approaching it

from behind at a shallow angle. The comet fragments, she explains, will be

approaching Jupiter's South Pole at an angle and hitting on the far side that

we cannot see.

However, due to Jupiter's rapid rotation, each comet

fragment crash site will come into view shortly after impact, allowing Earth-based

observers and telescopes to see the effects of those impacts within five or ten

minutes.

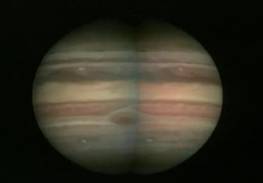

A video is presented in which a colorful Jupiter spins on

its axis. This is a composite of five high-resolution images taken from the

Hubble Space Telescope. A computer enhancement was used to knit the images

together and project them onto a sphere. Heidi apologizes that the image is

rougher than it could be. It was created by Eric de Young from data received

just 18 hours ago, so they haven't had time to clean it up yet. The planet is

divided into segments, like an orange. At each division, a diffuse vertical

line with bluish overtones is seen.

A video is presented in which a colorful Jupiter spins on

its axis. This is a composite of five high-resolution images taken from the

Hubble Space Telescope. A computer enhancement was used to knit the images

together and project them onto a sphere. Heidi apologizes that the image is

rougher than it could be. It was created by Eric de Young from data received

just 18 hours ago, so they haven't had time to clean it up yet. The planet is

divided into segments, like an orange. At each division, a diffuse vertical

line with bluish overtones is seen.

The spinning Jupiter image shows the planet's appearance

before the comet impacts. Heidi proudly points out that the image demonstrates

the "amazing quality of the images from the Wide Field Camera" of the

Hubble Space Telescope, and I marvel at its detail. The planet has an orange

hue, with bands of lighter and darker color encircling it. I watch for the Great

Red Spot to appear, that famous storm on Jupiter. In this color image, it is

readily identifiable as it slowly spins past, appearing as a large, orange-tan,

squashed oval just below the equator.

The dramatic image of the Fragment A impact site is

displayed again, and Heidi makes no attempt to conceal her excitement: "It's

a new feature on Jupiter," she smiles. "And we're going

to have twenty more of them ... even brighter ... "

"It's going to be a great week!"

The NASA briefing is being broadcast live from the Space

Telescope Science Institute (STSI) in Baltimore. Moderator Don Savage of the

NASA Public Affairs Office introduces the other five panelists on Heidi's team.

Each is a member of at least one or two Hubble Space Telescope camera and

spectrograph teams. Three are affiliated with the Space Telescope Science

Institute: Dr. Hal Weaver, Dr. Keith Noll, and Dr. Melissa McGrath. Seated between

those last two are Dr. John Clark of the University of Michigan and Dr. Bob

West of Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The NASA briefing is being broadcast live from the Space

Telescope Science Institute (STSI) in Baltimore. Moderator Don Savage of the

NASA Public Affairs Office introduces the other five panelists on Heidi's team.

Each is a member of at least one or two Hubble Space Telescope camera and

spectrograph teams. Three are affiliated with the Space Telescope Science

Institute: Dr. Hal Weaver, Dr. Keith Noll, and Dr. Melissa McGrath. Seated between

those last two are Dr. John Clark of the University of Michigan and Dr. Bob

West of Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Dr. Hal Weaver reinforces Heidi's prediction with his own

enthusiastic proclamation. "First of all, I'd just like to say it looks

like this comet was not a dud!" Hal says exuberantly as soon as he has the

floor. "Let it ring out to the rest of the world!" He goes on to say

that there's no evidence from the Hubble Space Telescope to support those

earlier reports that the comet chunks were breaking up.

Hal contends that the height of the plume that was imaged on

the first Hubble sweep provides "very strong evidence" that the

fragments are penetrating deeply into Jupiter's atmosphere. He believes a

broken-up comet fragment would not have been capable of creating such a huge

plume nor penetrating so deeply.

The excitement of the Hubble scientists is vividly demonstrated

in a video that shows them seeing the Fragment A impact site images for the

first time. Imagine the scene. All the team members have done their very best

to carry out this first experiment. They have commanded the Hubble to point in

what they hope will be the right direction, using what they hope

will be the right equipment, based on the best impact timing predictions available...

all on the off chance that there might be something to see, and that they

might get lucky enough to actually capture it. But given the relatively

small size of Fragment A, along with the possibility that it might have already

disintegrated, they are not expecting much.

Now it's time to see the fruits of their labor. A half dozen

faces stare intently at a computer screen that we can't see, because it's

facing away from us. Dr. Heidi Hammel is closest to it; she points at a spot on

the screen that corresponds to the latitude where the fragments should be

hitting. "This is the latitude [where] we're looking for something --

right there," she states. All eyes remain glued to the screen. Then --

"Look!" Heidi breathes. Her voice goes up several

pitches: "Look!!"

Behind her, Dr. Melissa McGrath gasps, "Oh, wow!"

"Oh, my God! Look at that!" Heidi exclaims. Her

excitement and disbelief is mirrored in the shocked expressions on all the

other faces.

As realization dawns, the room erupts into excited shrieks,

cheers, and claps. The commotion dies down, only to resume several seconds

later when another unexpected sight is revealed.

Expressions of amazement abound: "Wow!" "Oh, my

God!" "Did you see it?" "Look at it!" "I don't

believe this!" "Whoa!" "Unbelievable! Wow!"

Jubilation reigns.

Cut to a celebration. Heidi and Melissa together uncork a

bottle of champagne. Heidi takes the first swig and holds out the bottle towards

Melissa. The film stops before we get to see how the rest of this scene plays

out.

Cut to a celebration. Heidi and Melissa together uncork a

bottle of champagne. Heidi takes the first swig and holds out the bottle towards

Melissa. The film stops before we get to see how the rest of this scene plays

out.

I am amazed that they showed it at all. Do they really want

that broadcast on national television? Besides, don't any of those revelers

care about poor 'ol Jupiter? That planet has just experienced a cataclysmic

disturbance the size of our own Earth!

Yet the video has an honesty about it that is altogether

charming. In this age of carefully prerecorded sound bites, it is refreshing to

get an uncensored glimpse of scientists in their less conservative moments,

caught up in the excitement of discovery. Too often, we see only the serious

side of science, when the findings have already been made and dissected, when

the excitement has faded, when the human element has been filtered out. I'm

already beginning to like this NASA Channel for allowing me to observe science-in-the-making.

Next, members of the audience are invited to ask questions. Given

that the Hubble was able to capture signs of the first impact a couple of hours

after it occurred, a reporter asks whether the residue from the comet impacts might

remain visible on Jupiter a lot longer than anticipated. Dr. Bob West

hypothesizes that we might still be seeing residual effects from the comet "a

year from now." That's a far cry from today's earlier predictions that we

might not see anything at all!

Bob Cook from Newsday asks if the comet fragment

might have penetrated into the water clouds that scientists believe exist deep

in Jupiter's atmosphere. Dr. Keith Noll responds that evidence of the water

clouds is something that they will be "looking for very keenly."

"If we see a huge increase in the amount of water, more

than could have come from the comet itself," says Keith, "we'll know

something about the energy of the impactor and how deeply it penetrated into the

atmosphere."

Keith says that scientists also hope the comet fragments

will penetrate deeply enough into Jupiter's atmosphere to "churn up"

chemicals and "possibly allow us to see molecules that until now have been

too deep in Jupiter's atmosphere for us to sense remotely."

An unidentified reporter voices the question that is

foremost in my mind: "In the past few weeks, we've been told that amateur

astronomers have little chance of seeing this event," he observes. "Does

what you've seen so far make you a little more optimistic about what the

unwashed masses, or the 'semi-washed' masses, might see?"

Dr. Melissa McGrath takes the question. "The most

dramatic results we've seen so far, brightness-wise, have actually been in the

infrared," she states. In visible light, she believes, "it's unlikely

that this would have been seen." Her thinking is that the plume was very

small and close to the bright planet, which would require the high resolution

of the Hubble Space Telescope in order to see it.

But she would love to be proven wrong. She steals a quick

glance at her watch. "We know that the B impact is at 10:30," she states,

casting a meaningful glance at her colleagues, "and some of us

would actually like to go outside with our binoculars at 10:30 and look!" Laughter

erupts. "Because B's a lot bigger than A!" With 10:30 less than ten

minutes away, it's no wonder Melissa is on edge. Noting that Fragment A wasn't

as bright as B in visible light, she reiterates, "I think we should all go

look!"

It is more of a plea than a proposition. As heartbreaking as

it must be for her to miss this opportunity, she is too much the professional

to just march off the set and go outside. Alas, everyone else on the panel

seems to be determined -- or resigned -- to stick it out for the remainder of

the press conference. How can these astronomer-scientists be so composed, I

wonder, when they're on the verge of missing their one opportunity in a lifetime

to watch a comet hit a planet?