This morning's "Comet Impact '94" press conference

at 10:00 brings new faces, new data, and new questions as the scientific

process continues to unfold. For the rest of this week, these live NASA

briefings will originate from the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, in

the Washington, D.C. suburbs.

Today's panel features the three co-discoverers of Comet

Shoemaker-Levy 9: Dr. Eugene ("Gene") Shoemaker and his wife Dr. Carolyn

Shoemaker, both Lowell Observatory astronomers and U.S. Geological Survey scientists,

and amateur astronomer and author David H. Levy. Heidi Hammel is back for

another round, but the rest of the Hubble team have vanished. Are they finally

getting some sleep?

Gene Shoemaker starts with a recap of yesterday's fantastic

events. So far, Fragments A, B, C, and D have hit Jupiter.

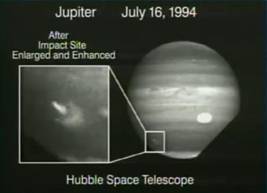

Heidi reviews the blue wavelength image we saw yesterday,

then presents some new images from Hubble. The first is in the methane band, which

is a red wavelength. It shows the Fragment A impact features as bright, the

opposite of how they look at other wavelengths observed by Hubble. Heidi explains

that bright features in the methane band are typically high-altitude features,

like the Great Red Spot and the poles.

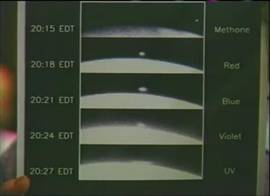

Next is the plume sequence mentioned last night that Heidi

says "knocked our socks off." It is a series of individual images taken

at different wavelengths that, when viewed together, chronicle an unmistakable chain

of events.

The first image was taken just before Fragment A struck Jupiter. It

shows a close-up of the bright edge, or limb, of Jupiter, with a small bright

circle -- the comet fragment -- approaching it from the right. The second image

was taken three minutes later, just after the impact. The circle now appears

near the center of the image, just above the limb of the planet. It is larger

and somewhat brighter. This is the so-called "fireball" rising above

the planet's atmosphere. In the next three images, each taken three minutes

apart, the circle gets brighter, then dims and flattens out as it falls toward

the planet.

The first image was taken just before Fragment A struck Jupiter. It

shows a close-up of the bright edge, or limb, of Jupiter, with a small bright

circle -- the comet fragment -- approaching it from the right. The second image

was taken three minutes later, just after the impact. The circle now appears

near the center of the image, just above the limb of the planet. It is larger

and somewhat brighter. This is the so-called "fireball" rising above

the planet's atmosphere. In the next three images, each taken three minutes

apart, the circle gets brighter, then dims and flattens out as it falls toward

the planet.

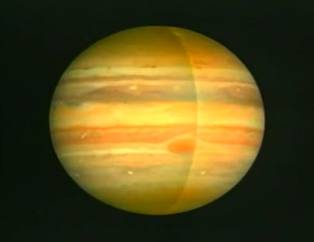

A cleaner, brighter orange Jupiter rotates slowly in an

improved version of yesterday's flick. Then they rerun the video of the Space

Telescope team seeing the first images from Hubble.

Carolyn Shoemaker provides narration.

Again, we watch Heidi and the other team members get wide-eyed and exclaim and

clap and shout. Next comes the clip with what Carolyn refers to as "the

infamous bottle of champagne." Obviously, I was not the only one who was

surprised to see that scene on television. But it captures the mood of that day,

for, as Carolyn puts it, "Everyone was ready to celebrate!"

Carolyn Shoemaker provides narration.

Again, we watch Heidi and the other team members get wide-eyed and exclaim and

clap and shout. Next comes the clip with what Carolyn refers to as "the

infamous bottle of champagne." Obviously, I was not the only one who was

surprised to see that scene on television. But it captures the mood of that day,

for, as Carolyn puts it, "Everyone was ready to celebrate!"

Co-discoverer David Levy is given the floor immediately

after the champagne video is run. He turns to Heidi with a smile and deadpans: "Heidi,

we have to work on getting you a little more enthusiastic about this!"

But now it's David's turn to get enthusiastic. "I

thought I'd have to make stuff up," he reflects, "but I don't know if

I'm going to say everything that I need to say." Like Heidi, he is

delighted that even that small first fragment's impact has turned out to be so

readily observable. He makes several references to the image behind the

panelists that shows the chain of comet fragments and each fragment's relative

size and brightness. "This is just the orchestra warming up," he says.

David states that there have been at least two reports by

small telescope users of a possible brief flash seen near the limb of Jupiter. Trying

to remain objective, David cautions: "I don't want to put a whole lot of

credence into it just yet until we get other observations of other flashes."

More confirmation is needed, he says, so "this is a red alert for

amateur astronomers with small telescopes!"

Lots of reports are coming in from observatories around the

world, and the panel presents them.

Dr. James Graham of the University of California gives a

video report from the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. He

describes the A and C fragment impacts as "incredibly bright, very

clear" and overall "a very spectacular event."

An infrared image from the Keck Telescope shows the A and C

impacts as bright spots near the bright southern pole of the planet. The Great

Red Spot appears on the right, just below the equator, but the impact sites are

much brighter. It's a dramatic shot.

An infrared image from the Keck Telescope shows the A and C

impacts as bright spots near the bright southern pole of the planet. The Great

Red Spot appears on the right, just below the equator, but the impact sites are

much brighter. It's a dramatic shot.

Gene Shoemaker observes, "It's very clear that these

impact sites are going to remain visible," noting that the Fragment A

impact site has undergone a complete rotation of the planet, yet it still looks

sharp.

Gene is

pleased with the plume sequence images because they provide good empirical data

against which theoretical models and predictions of meteor impact dynamics can

be compared. With glee, he

states that the plume sequence images show "the prediction is bang-on!" The fireball has arisen to a

"tall column" and then collapsed in the same manner and with the same

timing as the scientific models predicted. He proudly dubs the plume

pictures "a beautiful testimony to

the prediction that was made by Paul Hassig of Titan Research Corporation."

Kathy Sawyer from The Washington Post wants to know the

altitude of the "dark splotch" at the Fragment A impact site, and

what's in it. Gene replies that the dark spot should contain matter from Jupiter's

atmosphere "that has been dredged up from beneath the ammonia cloud tops,"

as well as "almost all of the cometary material." The impact would

have generated heat "in the range of 30,000 degrees Kelvin,"

resulting in exotic chemical reactions "we don't really know how to

model." The altitude of the spot is probably "on the order of a

couple hundred kilometers above the ammonia cloud tops."

A reporter from Reuters asks if there will be any permanent

effects on Jupiter from these comet impacts. "We won't know for a few

days" how long these features might last, Heidi explains. Jupiter's strong

winds could smear them. "Just from the few that we have seen," she

adds, "that whole band of latitude is going to be pockmarked with these

impact sites!" Momentarily at a loss for words, she shakes her head. "Heaven

only knows what I'm going to show you a week from now!"

David Levy, careful to temper his own enthusiasm, interjects

his expectation that the impact sites will "disappear within a matter of

days or weeks."

"I don't think Bob West would agree with that!"

Heidi fires back with a smile. She points out that after the eruption of Mt.

Pinatubo, "we were seeing beautiful sunsets for a very long time." Therefore,

it seems quite possible that signs of the comet impacts "could hang around

in the stratosphere of Jupiter for a while." In anticipation of that, the

Hubble Space Telescope and some ground-based telescopes have already been

programmed to keep checking for long-term effects, she notes.

Surprised by this prediction, Levy exclaims, "I'm going

to stop being conservative!"

On the other hand, there seems to be a shortage

of observations of the Fragment B impact. Perhaps that one really did

fizzle. Shoemaker speculates that it might have been a "swarm of

objects" instead of a solid one.

An unidentified reporter asks an excellent question: How can

a comet impact result in a "fireball" when there is no oxygen on

Jupiter?

David offers clarification. When the fragment first reaches

the planet's stratosphere, it "starts to interact with the

atmosphere," producing a "very, very bright meteor" as it heats

up. Then it disappears below the clouds and "explodes somewhere well below

the clouds." This creates a huge plume that rises above the clouds and

lingers for a few minutes. "That we call the fireball," Levy explains.

"It's just a terminology that comes from nuclear

experiments," Gene interjects. "It doesn't mean that something is

burning. It's just extraordinarily hot. The heat is coming from the shockwave,

not from combustion. It's incandescent because it's so hot."

Could the smudgy arc around the central A spot in the

blue-filtered image be a seismic wave? Heidi and Gene engage in an animated

debate.

"Well, you saw the seismic wave," says Gene,

pointing at the image. "There it is!"

"Where?" asks Heidi.

"Right down there around your spot!"

"Not!" counters Heidi.

They both laugh.

"We were primarily expecting to see the seismic waves

and the atmospheric waves in the infrared data," elaborates Heidi. "That's

where you would directly detect the seismic waves. And in this visible

wavelength data, you're seeing a secondary effect, where the temperature causes

some kind of cloud to condense in the atmosphere. From what I have heard and

seen so far, we have seen the impact sites in the infrared, but I have

not yet heard a report of seeing wave phenomena in the infrared [images]."

"OK, now, Heidi --" Gene demands, pointing at the

image, "What's that ring around the dark spot?"

" Well ... " muses Heidi, "that's a good

question!" She laughs.

"I claim that's just about the distance at which the

acoustic wave should have arrived," Gene asserts.

"Well, we'll know when we have another sequence of

images where we can see that expand outward," says Heidi. "If we

don't see that moving outwards, Gene, then it's not likely to be an atmospheric

wave."

Suddenly defensive about not having produced just such a

sequence for Fragment A, Heidi wails, "This isn't the best one! We

didn't expect to see anything! We didn't plan a sequence."

More calmly, she explains that later in the week they are

"planning to take sequences over several orbits so we can see this wave

move out."

"So we're going to have to wait and see," she

concludes, adding, "You can believe anything you want in this

photograph!"

"You have to explain why that [ring] is out as far out

as it is," Gene persists, repeating his assertion that the ring is located

about where he would expect an acoustic wave to show up.

Heidi is still not convinced. "Okay, I'll go out on a

limb here," she states. "I thought...that was debris that had fallen

down. I mean, when we looked at that plume image, it [was] very

extended. And I thought...that circular pattern was the fallout from that

plume."

Gene smiles. "Okay. We'll see. I'm betting it's a

seismic wave. You're seeing an effect in the atmosphere due to the acoustic

wave."

Heidi smiles back. "We'll see."

"Okay," says Gene.

They both laugh.

Once again, we are getting an uncensored glimpse of how

science is practiced.

Stretching along the wall behind the

panelists is a composite image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope depicting Comet

Shoemaker-Levy 9's chain of glowing fragments, dubbed the "string of

pearls" by scientists.

The fragments that appear to be the brightest

-- such as G, H, K, and Q -- are presumed to be the largest. These

fragments are expected to be about three kilometers long, whereas

Fragment A is only supposed to be about one kilometer. According to Heidi,

Fragment A turned out to be "much more energetic than we expected,"

on the order of what had been expected for the much larger Fragment G. Given

that G looks much brighter than A, we could be in for some impressive fireworks

this week!

The fragments that appear to be the brightest

-- such as G, H, K, and Q -- are presumed to be the largest. These

fragments are expected to be about three kilometers long, whereas

Fragment A is only supposed to be about one kilometer. According to Heidi,

Fragment A turned out to be "much more energetic than we expected,"

on the order of what had been expected for the much larger Fragment G. Given

that G looks much brighter than A, we could be in for some impressive fireworks

this week!

A reporter from the Miami Herald asks what would have

happened if something the size of Fragment A had hit North America.

"If A had hit North America," says Gene, "it

would have made a crater about 20 kilometers in diameter.

"Of course, if that happened over the

Baltimore-Washington area, it would have taken us all out. We wouldn't be here.

So the local damage would have been just enormous.

"You not only take out what's in the crater, but you

take out everything that's in the ejecta blanket of the crater [the area around

the crater that gets covered with debris thrown out by the explosion], and you

knock down things for ... hundreds of miles beyond that," Gene continues.

"A tremendous amount of pulverized material would have been carried up

into the high atmosphere, and ultimately would spread over all of the northern

hemisphere. You'd probably get a very significant global climatic effect from

that single fragment."

"So," Gene summarizes, "it would be a major

disaster -- probably the worst natural disaster ever witnessed by man."

The four panelists sit in somber silence digesting that.

"And that's just for a single, tiny first

fragment that we didn't expect anything from," muses David.

Updated impact times

for the next three fragments are provided. Fragment E is expected to hit

at 11:05 this morning and Fragment F will hit at 8:27 this evening. The big

one, Fragment G, won't hit until

3:29 a.m. tomorrow.

David Levy reiterates that "observers with small telescopes

should be trying to watch at the right spot on the limb for brief flashes" from the comet

impacts. He cautions that Jupiter will

not suddenly get a lot brighter, but that "if you really know what

you're looking for, there is a chance that you might detect the flash."

"There have

been no reports from any professional observatories detecting those flashes,"

Heidi qualifies, "and they've been looking!"

Carolyn mentions

that she and Gene were at the Naval Observatory last night and "put our eye to the telescope in

hopes of seeing a flash."

"When you

really want to see a flash, you can almost imagine that you do,"

she warns. "So we all have to be careful that we aren't imagining

something that isn't quite out there."

Nevertheless, amateur observers have some advantages over

professionals at observatories. "The

visual observer has the advantage of being there watching all the time," Gene points out. That allows them to catch fleeting events

that only last a couple of seconds -- events that professional observers

and equipment could easily miss

if they were not actively monitoring Jupiter at the time.

The Hubble Space

Telescope was not designed to record "very rapid time sequence" images,

Heidi notes in response to the next reporter's question. Referring to

the Hubble's images of the Fragment A

plume sequence, which is basically just a collection of pictures taken

at different wavelengths, she observes that it was "purely serendipitous

that we did see it in a time sequence like that."

At the close of the briefing,

the video images are rerun, and for the fourth time in two days,

we see that "infamous

bottle of champagne" from the Fragment A celebration.

Once again, I contemplate those markings on Jupiter from Fragment

A. Surely you could see them if you had a big enough telescope ... couldn't

you? The largest fragment is supposed to be Q, and it won't arrive at Jupiter

for another couple of days. If I were to purchase a telescope and learn how to

use it, could I not see the markings from Q? But how do you buy a

telescope? And where? Is there such thing as a telescope store?