Is my three-and-a-half-inch telescope large enough to see

the spots on Jupiter? That question is foremost in my mind as I sit down at

noon to watch today's NASA briefing. My father is watching, too.

Don Savage opens the program as usual and introduces the

panelists. Dr. Steve Maran is back as moderator, and Dr. Lucy McFadden has also

returned to deliver news updates. Shoemaker-Levy 9 co-discoverer David Levy is

back after an absence of several days. Newly arrived are Dr. Roger Yelle of the

University of Arizona, who is part of the Hubble Space Telescope's Spectroscopy Team, and Dr. Renee Prange from the

French Institute Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France, who is a member

of the Hubble Space Telescope's Upper Atmosphere Imaging Team.

Steve states that Fragment P2 should have hit Jupiter within

the past hour, and that the triple-shot sequence of the Fragment Q, R, and S impacts

occurring ten hours apart will begin today at 3:32 p.m.

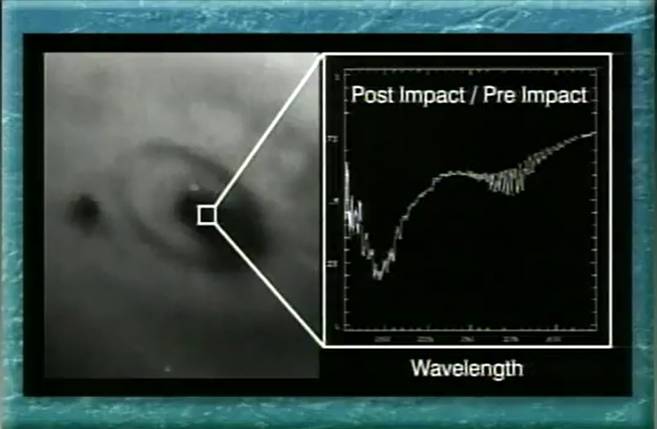

Dr. Roger Yelle has a new discovery to report. A new graph of

spectroscopic data from the Fragment G impact is displayed, taken by the Hubble

Space Telescope's Faint Object Spectrograph in the 150 to 3000 nanometer

wavelength range (ultraviolet light). It follows the same format as yesterday's

spectroscopic results, in the form of a curve that dips to show how much less

light at certain wavelengths is present after the comet impact, compared with

before. The deepest dip is the ammonia dip we saw yesterday, at around 200

nanometers. However, this graph includes a wider range of wavelengths, and there

is a plateau to the right of the ammonia dip. The right part of that plateau

consists of a number of closely-spaced wiggly lines -- "it looks sort of

like a fishbone," says Roger -- in the vicinity of 270 nanometers. That

indicates absorption by some other type of molecule. It "was very exciting

when we saw that yesterday," relates Roger, "but we had no idea what

it was."

nanometers. However, this graph includes a wider range of wavelengths, and there

is a plateau to the right of the ammonia dip. The right part of that plateau

consists of a number of closely-spaced wiggly lines -- "it looks sort of

like a fishbone," says Roger -- in the vicinity of 270 nanometers. That

indicates absorption by some other type of molecule. It "was very exciting

when we saw that yesterday," relates Roger, "but we had no idea what

it was."

Roger gives a very thorough introduction to this new

discovery. "Molecules will absorb at specific wavelengths -- specific

colors -- that are their own signature," he states, "so one molecule

will absorb at one wavelength; another molecule will absorb at another

wavelength." The shape of this new signature offers some clues as to the

nature of the molecule that's causing it. "It's a very regular spacing of

ripples, and that tells you that it's a simple molecule," explains Roger. "Secondly,

the ripples are close together, and that tells you that it's a heavy

molecule."

He describes the curve and the challenges the researchers faced

in determining which substance those wiggles represented. It wasn't something

that they were expecting, so they "had to go off and search spectra of all

the molecules [they] could think of to find out what [it] was -- and none of

the simple ones matched up!" It wasn't until "about 3:00 in the

morning" that they began to put the pieces together on the nature of that

molecule ...

Dad sits calmly through this entire discourse, unaware of

how tantalizingly few solid findings have come out of these early comet impact

observations. But I am in an extreme state of suspense. Is it water? If not

water, then what is it? Is it part of the comet? Part of Jupiter's

atmosphere? It must be something pretty exciting or unusual if they didn't

think to look for it right away. This is one of the richest finds we've had

yet: a tangible clue to the chemistry that has been going on. But Roger is

taking his time in telling us, drawing out the story.

Finally, after keeping us in suspense for five

excruciatingly long (to me) minutes, he divulges the substance's name.

"Those features are a very good match to the spectrum of sulfur ... sulfur gas," Roger states.

More specifically, it's a diatomic sulfur molecule -- a pair of sulfur atoms bonded together.

Is this sulfur gas from the comet or from Jupiter? It could

be either one. "Sulfur is seen in most comets, I believe," offers

Roger, but he says that Jupiter's atmosphere also contains sulfur.

Roger notes that there appears to be yet a third type of molecule

in the vicinity of the ammonia one, and that while it could yet turn out to be

something else, "the spectrum is consistent with the presence of hydrogen

sulfide."

There is still no sign of water at the impact sites. By now,

this absence of detectable water piques my curiosity almost as much as it does

that of the scientists who have been continually searching for it.

After Dr. Roger Yelle, it is Dr. Renee Prange's turn to

speak. "Jupiter, like the Earth, is a strong magnet," Renee begins. Like

the Earth, it experiences auroras at its poles.

We now see black-and-white

images of the auroras of Jupiter, taken by the Hubble's Wide Field and

Planetary Camera 2 in the far ultraviolet. The first image was taken before the

comet impacts, and it shows the auroras at Jupiter's North and South poles. I

think it's the same one we saw Monday morning, that "best-ever" image

of Jupiter's auroras.

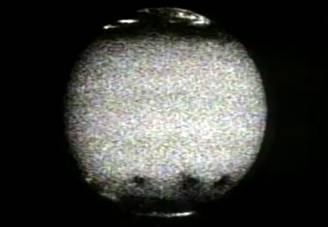

The second image looks a lot like the "after" image of the auroras that we saw on

Monday, with one startling exception: two bright areas have appeared below and

to the left of the polar aurora at Jupiter's North Pole!

This presents no small mystery: if the comet fragments are

impacting Jupiter near its South Pole, then why would there be two

bright auroral spots near the North Pole? They are further south than

any other North Pole auroras have ever been observed. How did they get there?

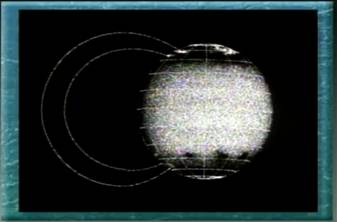

Renee Prange has some theories, so now it's her turn

to hold forth for a while. She has already stated that Jupiter acts like a

giant magnet, as does the Earth. Any magnet has a north pole and a south pole,

and magnetic field lines pass through a magnet from its south pole to its north

pole. But they don't just stop there; they arc through space from one pole to

the other, completing a loop.

Renee's theory is that charged particles from the comet

fragments have been propelled along the magnetic field lines from their origins

near the South Pole all the way around to a corresponding latitude in the North

Pole region. "Some material from the comet itself was liberated at the South

Pole, accelerated ... around these magnetic field lines, and fell into the

northern hemisphere," Renee theorizes. A third image is shown that

illustrates these hypothetical magnetic field lines.

near the South Pole all the way around to a corresponding latitude in the North

Pole region. "Some material from the comet itself was liberated at the South

Pole, accelerated ... around these magnetic field lines, and fell into the

northern hemisphere," Renee theorizes. A third image is shown that

illustrates these hypothetical magnetic field lines.

"I think it's a major discovery," Renee asserts.

Less scientifically intriguing but even more exciting to me is

the latest news from the amateur astronomy world. The impact spots on Jupiter

can definitely be seen now from amateur telescopes!

David Levy introduces this topic by commenting that it

almost feels as if they are all competing in some sort of contest to come up

with the biggest surprise of the week.

"I can't say that the fact that these dark spots are

visible for virtually everybody to see is the biggest surprise," he

says humbly, eyes alight with happiness, "but it sure is one of the

biggest ...

"Nobody expected this."

"We have some very large spots on Jupiter,"

David amplifies. "By now there are enough of these spots that no matter

where you are, when Jupiter is in the sky after dark, you will probably be

seeing some spots." He notes that Clark Chapman has been observing Jupiter

for many years, and he paraphrases Chapman's label of the Fragment G impact site

as "the most obvious feature ever to appear on this planet." According

to Levy, Chapman has challenged everyone on the Internet to argue that claim. "So

far, nobody has!" Levy notes happily.

"If you have any experience at all looking at

Jupiter," says David, "these spots should be extremely easy to

see."

Levy wonders what might have happened had the comet

fragments not been discovered ahead of time. "If the comet had never been

found," he muses, "right now, people would be seeing one spot after

another appearing on Jupiter." If it were just one spot, observers might

have guessed that a large object had hit the planet. "But these spots are

now forming all over that area of Jupiter," David points out, and if

anyone had dared to suggest that it was a series of separate impacts, others

would have responded, "No, how could you possibly get so many

impacts in the course of a week?"

Lucy responds generously. "I think we're lucky that

these guys were watching and found it!" she says, alluding to David and

the absent Shoemakers.

"If there has ever been a time to get out with a

small telescope and look at Jupiter -- ever since Galileo first observed

Jupiter through a telescope in 1610 -- this is the time to do it!"

David proclaims.

"This is just a marvelous time to be looking at

Jupiter!"

Lucy leads the rest of the news summary, which includes

additional images of Jupiter at different wavelengths, with impact spots

clearly visible.

Before presenting the latest report from the Kuiper Airborne

Observatory, Lucy describes the aircraft for us. A C-141 cargo plane that flies

at 41,000 feet, it has a compartment with a 36-inch telescope in it that can be

aimed through an opening in its fuselage. According to Lucy, "everyone

who's flown on it reports an exciting adventure."

"At 41,000 feet, they have oxygen within reach,"

Lucy enlarges. "[If] the interlock between the telescope and the observers

breaks, they have fifteen seconds to get their oxygen masks on."

One obvious advantage of this observatory is that it can fly

to wherever on Earth it is needed -- currently Melbourne, Australia. Dr. Gordon

Bjoraker of the Goddard Space Flight Center reports from Melbourne that another

advantage is that "you're flying above 99.9% of the water vapor in the Earth's

atmosphere, and you're above 80% of the total atmosphere.

"Our key thermometer is the methane molecule, which is

present in the Earth's atmosphere," Bjoraker adds. "By flying at

41,000 feet, this opens up a window where we can measure very strong methane

features on Jupiter that are not measurable from ground-based telescopes."

Dr. Anita Cochran of the University of Texas tells how she

and her colleagues at the McDonald Observatory in Fort Davis, Texas, had a ball

looking at Jupiter last night under outstanding observing conditions. "We've

mostly been running around like giddy little kids, because it's very

exciting to watch this," she confesses. "We've all had to take our

turns looking through the eyepiece, because you can see the structure of

the spots in the eyepiece ... and it's so much fun to watch Jupiter change [before]

our eyes!"

They did manage to take pictures of the Fragment L and

other impact sites. "The conditions turned spectacular very soon on, we

had excellent, excellent transparency almost all night and extremely

stable atmospheric conditions," she says. As a result, they obtained some

"really pretty images" using the 2.7-meter (8.8-foot) and 0.8-meter (2.62-foot)

telescopes.

They did manage to take pictures of the Fragment L and

other impact sites. "The conditions turned spectacular very soon on, we

had excellent, excellent transparency almost all night and extremely

stable atmospheric conditions," she says. As a result, they obtained some

"really pretty images" using the 2.7-meter (8.8-foot) and 0.8-meter (2.62-foot)

telescopes.

One striking image that Anita presents shows four spots plus

the Great Red Spot; it was taken with the infrared camera in a "hydrogen

molecular band."

"We sent this in the conventional orientation,"

Anita notes, then adds, "We find it amusing to turn this and some of the

other images upside-down and look at it. You'll see why when you see the

image."

The image is inverted as she speaks, and a goofy-looking

smiley-face appears! Laughter is heard from the panelists.

The image is inverted as she speaks, and a goofy-looking

smiley-face appears! Laughter is heard from the panelists.

"You turn it upside-down, and Jupiter doesn't seem so

unhappy, after all!" Steve later remarks.

Near the end of the question

and answer session, a reporter from Florida Today asks if there's any

evidence that the spots are fading. "We're going to ask Lucy McFadden to

answer that," Steve directs, "because Dave Levy was called away; he

is in great demand!" Sure enough, Levy has vanished from the set.

"There is evidence of fading of some of the spots,

changes in the brightness of some of the spots," Lucy acknowledges.

My pulse quickens at the thought of all those spots dimming.

Apparently it wasn't enough to buy a telescope; now I need the weather

to cooperate! A nice, clear observing window like the one they've been enjoying

in Texas would be wonderful ... and soon, before all those magnificent

spots fade away!